When it comes to classified data, officials are usually very tight-lipped, and rightly so. Some data is just not meant for the public (yet). Then again, there is some information that was never intended to be „acknowledged by the general public”, as one would say in official legal parlance. Still, a decommissioned laptop computer formerly used by the German armed forces ended up on eBay – including all the peripherals as well as its original hard drive for a “Buy Now” price of 90 Euros (approx. 100 USD).

Alexandra Stehr and Tim Berghoff have taken a closer look – and they unearthed some really interesting bits of information

Heavy Machinery

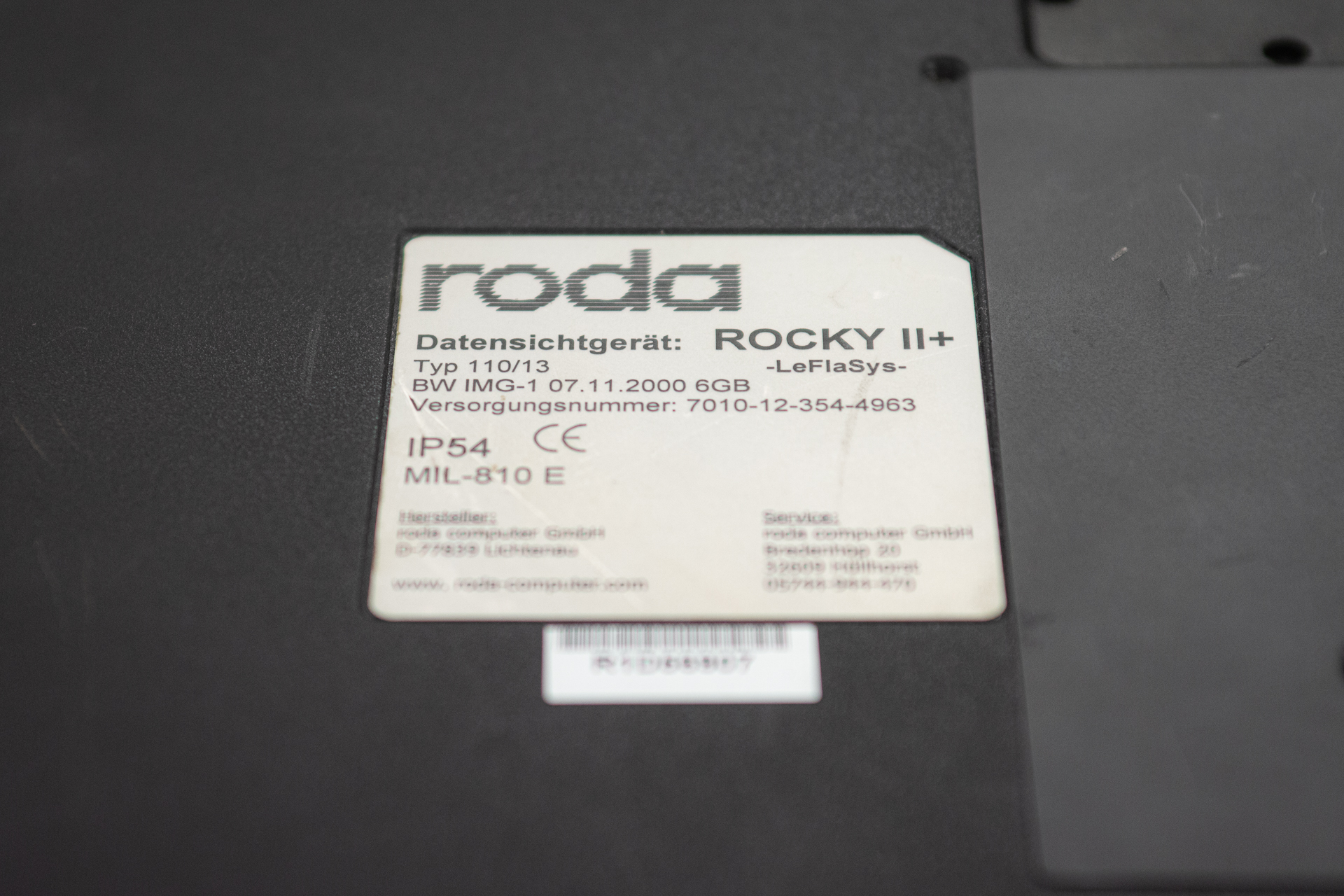

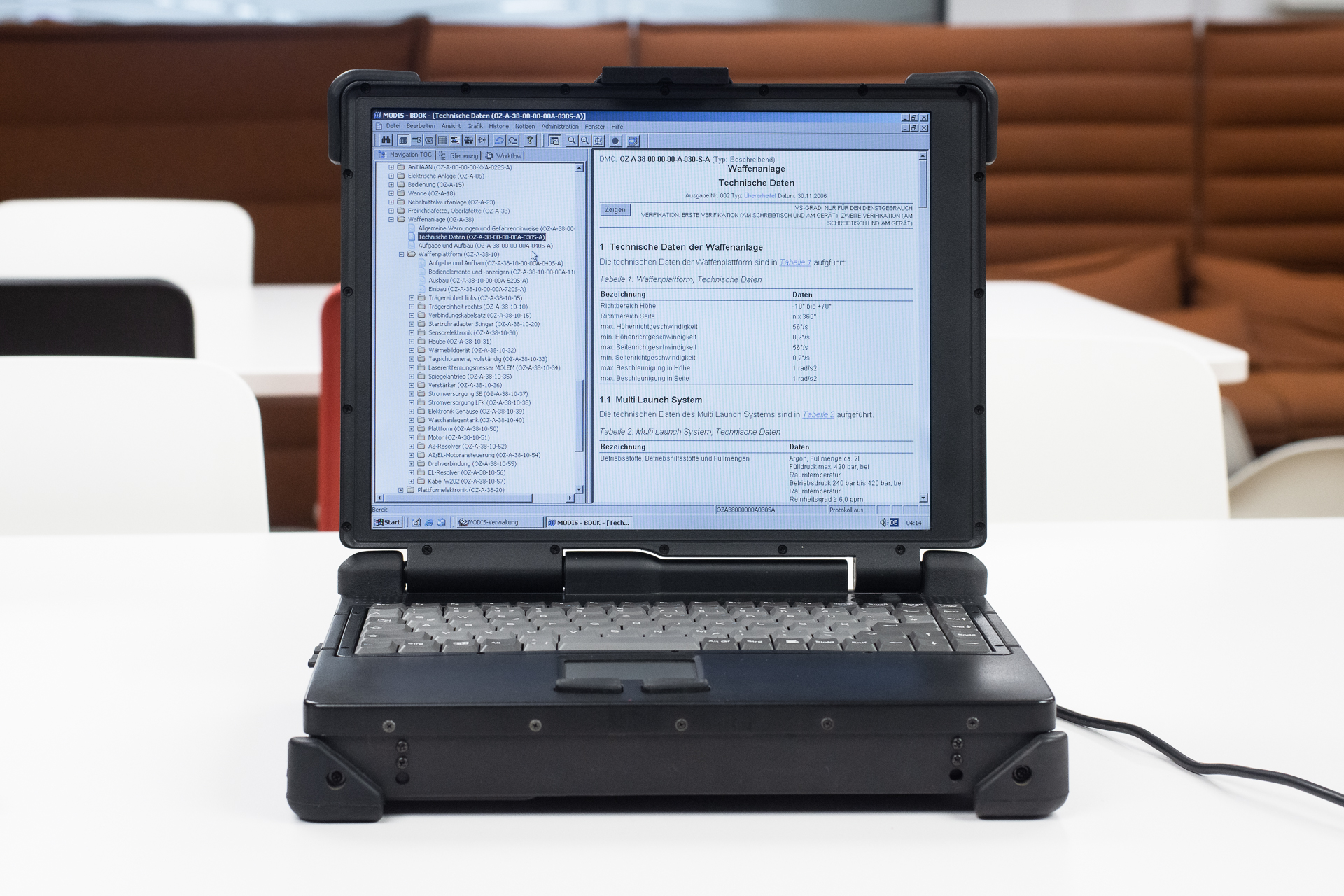

It is Monday, 4 pm when I enter the office of my colleague Alexandra. Our plan is to examine the hard drive of the machine. The laptop computer is well past its prime at this point and no longer fit for any meaningful work. Inside this behemoth of a laptop is a 600 MHz Pentium III processor, accompanied by 128 MB of RAM. This was "State of the Art" in the early 2000s, and it definitely was not cheap. For a retro gaming machine, though, this is still plenty enough. The device is even Soundblaster compatible. But this is not what we are here for – at least not yet. What makes this machinne so interesting is where it came from. A label at the underside of the laptop gives it away. It reads „Roda Rocky II+ Data Viewing Unit LeFlaSys“. The device used to be in service in the German armed forces. It came with a bunch of peripherals, such as a 3.5” floppy drive, spare batteries (which were unsurprisingly long dead by now), vehicle power adapter and other odds and ends. The notebook computer on its own weighs in at just under 5 kilograms (about 11 lbs) – not exactly what you would call “portable” today. But this is hardly a surprise. The machine is a so-called “fully ruggedized” laptop. Thick rubber bumpers all around, rubber caps covering all the external ports and a very sturdy carrying handle make it ideal for use in the field. It is splash and dust proof. This thing can surely take a beating.

Extrication

Alexandra and I immediately set to work. She unscrews one of the panels at the underside, expecting to find a hard drive there. What we find is a load of white-ish goop. Thermal paste, by the look of it. This makes sense – this machine is passively cooled and does not have any fans. Instead, a massive metal cooling block is what’s under this cover. After replacing it (and washing the sticky thermal grease off our fingers), we eventually find what we were looking for. Removing the hard drive only requires undoing one screw, using a coin. What we pull out is a caddy which holds the drive itself. This is very similar to what was used on older IBM Thinkpad models, so the concept is not completely new for us. The caddy is made of plastic and fully encloses the drive. Alexandra assumes that it is held together by little plastic snaps and carefully begins prying on one corner with a pocket knife. The cover won’t budge. It then turns out, the plastic is indeed secured in place by a couple of snaps – and very brittle. A large chunk of plastic suddenly flies off while attempting to widen the small opening we managed so far. “Well – that plastic isn’t getting any better over time“, Alexandra says shrugging. “Okay – it’s destructive entry, then“, I say and take over the prying action. Underneath the brittle plastic, the 2.5” hard drive comes into view. And my initial hunch is confirmed. I remark: „The drive is practically glued in there – there are these rubber and foam thingies all around the drive. Well, at least it’s not potted…that would really have been a pain.“ I attempt to liberate the hard drive by way of further prying, but – no dice. “I will try to cut through these bumpers“. Alexandra warns me: „Be careful – don’t get too close to that ribbon cable!” Her warning is justified – ribbon cables like this are quite sensitive and do not handle damage very well. Even bending them in the wrong place can damage them beyond repair.

„I won’t - don’t worry.“ I make quick work of the eight rubber pads that protect the drive from shocks and that hold it in place. Finally, the hard drive is free of its casing. We are looking at a 6 GB IDE drive made by Fujitsu. The thin and delicate connector pins end in an adapter which goes outside the case and into another connector, which then plugs the drive into the computer.

Securing

So far so good. “Let’s see what you’ve got” ,says Alexandra. She reaches into her bag and pulls out a special adapter which connects the old hard drive to a new PC over a USB connection. Of course, we had considered using a write blocker that is normally used by our forensics specialists. This is to ensure that the contents of the hard drive remains unaltered. After all, we did not want to mess this up. But then we were told that “You would only need this if you want to secure the data to make it court admissible evidence”. Since this was not our plan, we decided against it. Alexandra now connects the drive to her Linux machine and within minutes creates a byte-by-byte copy of the hard drive. That way, we have the contens of the drive, even if the hardware decides to give up the ghost after this.

From this point on, we are working in parallel: while Alexandra gets to work on the image she created, I put the drive back into the machine. What I want to see is whether or not this thing still works. “Right, time for the smoke test – here goes nothing...“, I say and hit the power button. And, lo and behold: the old computer springs to life and I immediately get feelings of nostalgia, when I am greeted by a Windows 2000 boot screen on a display that still works flawlessly. “Okay, I don’t see a login screen“, I call over to the other desk, where Alexandra is sitting. “We’re off to a good start already…” Indeed – there is no password protection on the system.

Once booting is complete, I see a tidy desktop in that unmistakeable light blue that was so common in Windows versions of days gone by.

Looking for data

Meanwhile, at the desk next to me, Alexandra calls over: „I’m looking for any data that may have been deleted!” This is a good plan. Owners of old machines often delete their files before disposing of them or selling them on. There is a catch: In many cases, the files are “deleted” by moving them into the Windows Recycling Bin and deleting them from there. This method of data disposal is not very effective, though. Most of the time, especially on hard drives that use magnetic platters inside, the data is still present after “deleting” it. What happens in the background is this: the operating system just removes the reference for the file and allows other applications to use the space formerly occupied by the supposedly deleted file. As long as no other data is written in that space, the files are in most cases fully recoverable. Modern SSD drives handle this differently. As soon as a file is marked for deletion, the drive will automatically see to that the area is overwritten. Not even cutting the power will preventi this. As soon as the drive is powered up again, the drive will automatically pick up where it left off and wipe the data. “So far I couldn’t find any deleted files“, Alexandra calls over. The disappointment in her voice clearly showing through. “If there was any data to begin with, it was either deleted really thoroughly or nothing was deleted at all.

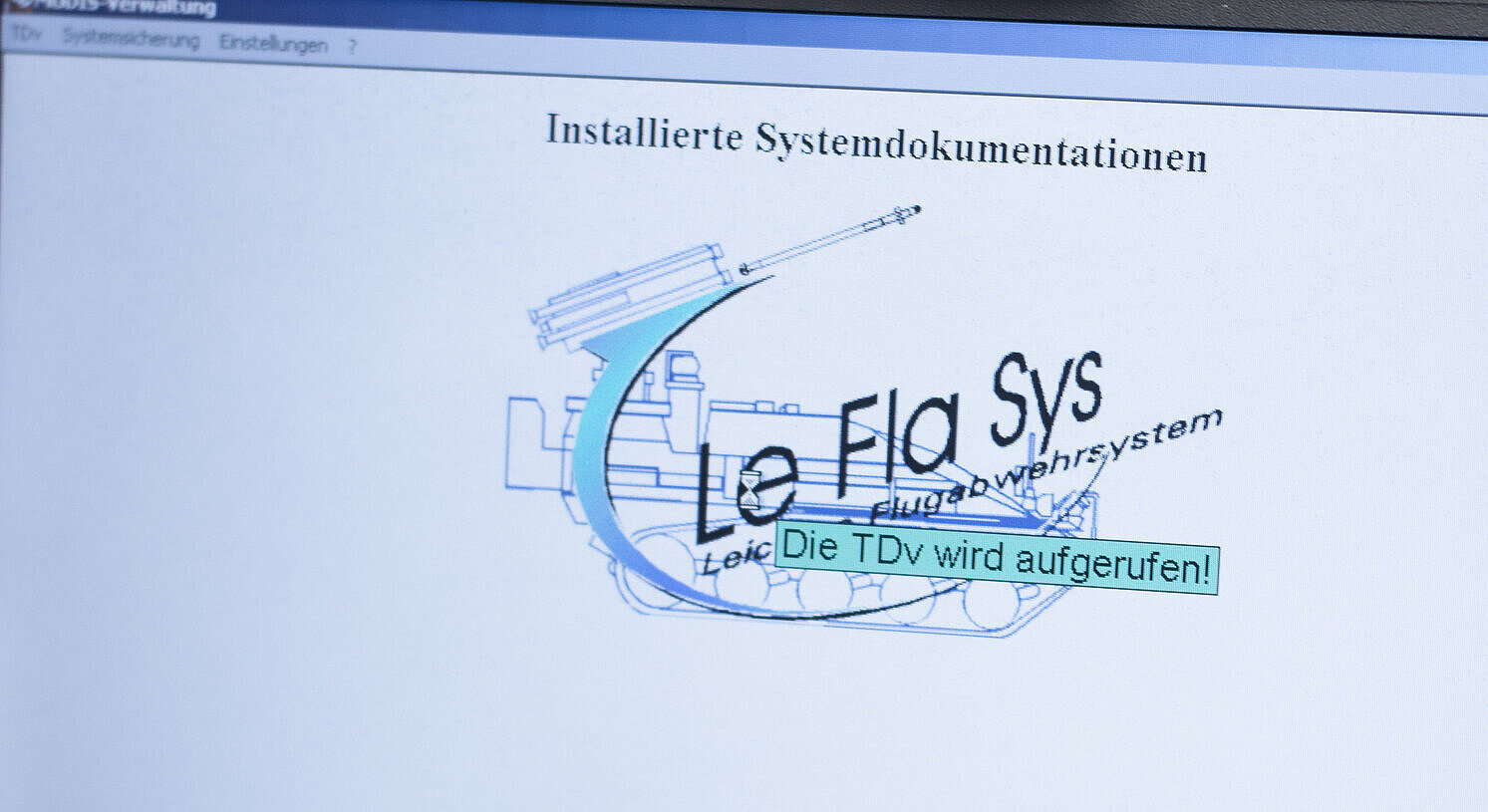

In the mean time I am taking a look around on the old machine. There is a version of Outlook installed. I am excited and open it – but am greeted by the setup wizard, which only shows up if no mail account has been configured. Bummer. Or is it? Another program peaks my interest: a piece of software called MODIS, made by a Munich-based company. On opening it, I get a password prompt. User name; “GUEST”. Alexandra pulls up her chair next to me. We look at each other and have the same thought. Quickly, the password „GUEST“ is entered on the machine – and we are in.

Properly deleting data is not rocket science, but someone needs to actually do it. This is where many companies and public organizations fail. This is completely beyond me.

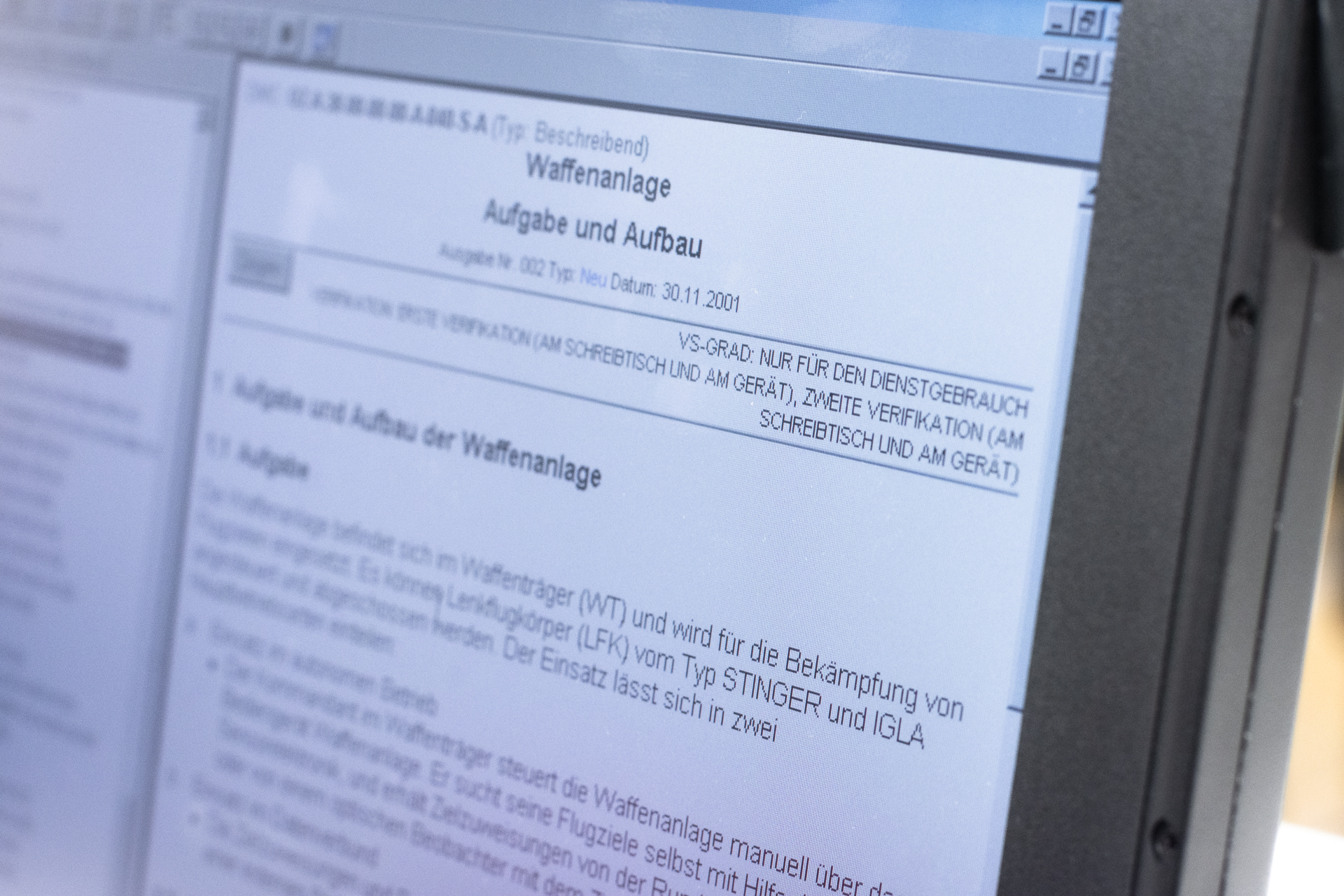

Classified

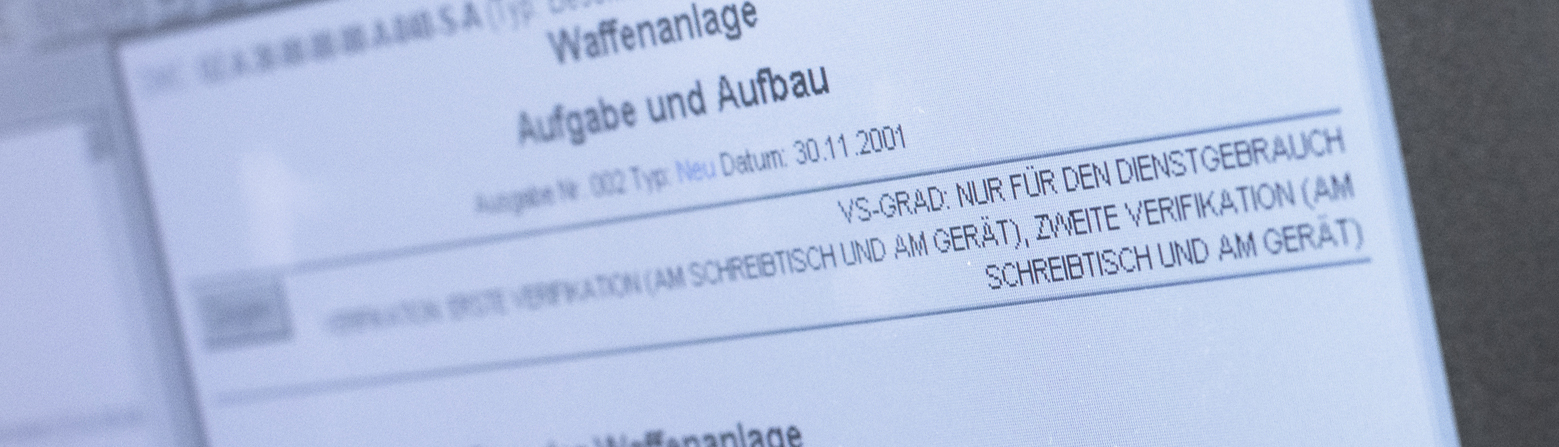

After a brief look around we have proof: what we have here is a complete documentation called TDv 1425/027-18. „TDv“ stands for „Technische Dienstvorschrift“, roughly translated „Technical Service Standards“. It is the military equivalent of a User Manual. This one belongs to a light Surface to Air missile system called „Ozelot“ (Ocelot).

We look around and find complete maintenance instructions, drawings and operating instructions. There are even schematics for the electronics in there, but those are apparently not stored locally, but on an external system. So we can’t take a peek at those. This weapons platform, according to the manual, can be equipped with „Mistral“ guided missiles and also has – as usual in army vehicles of this kind, a machine gun mount.

Alexandra is incredulous and remarks „This stuff was never intended for the public!“

Cats and the German Army

Following the naming traditions of the Bundeswehr, combat vehicles often get the names of predatory cats. The German armed forces have (and previosuly had) vehicles named Leopard, Puma or Panther – and of course, the ocelot.

But other animals are also present in this scheme: Weasle, Buffalo, Beaver, Boar, Badger or Marten.

She is right: on the top right, on every page of this documentation, there is a „classified“ marker: „Classified: Official Use only“. In other words, none of what we found here was ever intended to be viewed by the public. Remember: we had purchased the machine on a hunch, for about 100 USD (plus shipping). This is really a lesson in what not to do when disposing of hardware.

Is the information we found dangerous in any way? No. It is an operations manual for a piece of military equipment that nobody outside the armed forces has (or will ever have) access to. Some of the information can also be acquired through other sources. Other pieces of information may be interesting from a technical stand point (or just as “random trivia”) – such as the fact that the laser range finder of this missile system contains a pressurized vessel filled with methane gas. But we cannot see how any would-be attacker could gain an advantage by acquiring this information. The instructions are very detailed and explain exactly how to operate the missile system. There are chapters such as „Airspace Surveillance, manual/automatic“, „Target Acquisition / Target Acquisition from External Source”, “Deploy/Secure Weapons Platform”, “Calibration & Adjustment” as well as “Load Guided Missiles” and “Engaging Targets”.

Should this data have been destroyed when decommissioning the device? Yes, definitely.

What is "classified"?

In Germany, any piece of classified information falls into one of four categories. Those are based on the consequences that would result from the information becoming public:

- Classified – Official Use Only: publication of this data may cause minor disadvantages

- Classified - Confidential –Publishing the data can result in damages

- Classified – Secret – publication of the data results jeopardized safety&security

- Classified – Top Secret – Immediate existential threat when this information is made public

The data contained on this army laptop may have been classified at the lowest level – still, those in charge should have taken greater care when decommissioning it and removing it from the inventory by ensuring the destruction of the data.

It is not unheard of that storage media are sold on which have not been wiped and still contain critical information, so this is not exclusive to this particular case.

A more recent seach for similar machines turned out that we were apparently lucky. In almost all of the auctions we trawled, no hard drive was included with the device. So this case may be an exception from the rule. One thing is still certain: there are many hard drives still out there that were never wiped and still contain business-related or personal data that has no business being out in the open.

Data protection does not end with removing a device from the inventory list.

How to correctly dispose of storage media

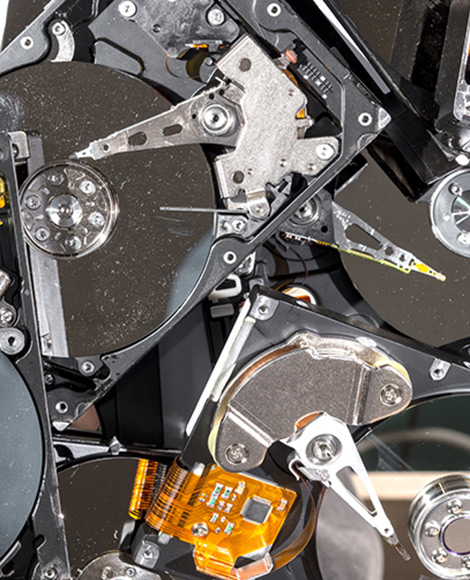

If you intend to write off and dispose of old hardware in your home or in your business, there are a few simple steps you can take. They do not cause a lot of trouble, but can save you lots of it.

- Remove hard drives from the device.

Modern network printers also often contain hard drives, which may even hold copies of the information printed with the device. - If the storage media are to be reused or sold on:

This works best when overwriting the drive with random numbers. Specialized tools for this are available, such as Darik's Boon and Nuke (DBAN). This ensures that no data can ever be recovered. And even if so, the cost will vastly outrun any potential benefits. - Destroy storage media

If you do not intend to reuse or resell the medium in question, it must be destroyed. There are several ways of achieving this. Magnetic hard drives can be wiped by running a strong magnet over it. For commercial use as well as for destroying classified material, hard drive shredding machines are available, which will physically cut the hard drive into small scraps of metal and plastic – including an automatic documentation of the destruction.

By the way: the documentation we saw also contained a chapter on making the system unusable to prevent use of the missile by a military adversary. Apart from obvious steps such as “destroy the vehicle using any available explosives”, “destroy sensor arrays with hammers or hatchets” and “cut fuel lines in the engine compartment and light any draining fuel on fire”, there is also a section which states “Remove any hard drives”.