A blast from the past

First off, it goes without saying that this was a remarkable incident in several respects. While the overall number of infected computers worldwide totals at over 200.000, we have to say that this might not have been the biggest malware outbreak in history. But it certainly is up there with the likes of the Sasser worm or Blaster in terms of the speed and ferocity with which it spread. For comparison, in 2003 the "Blaster" worm affected several million systems worldwide.

WannaCry has spread across the globe like wildfire and infected around 74000 PCs within the first 12 hours. One of the reasons that enable it to propagate at this blistering speed was the fact that it used code which came courtesy of some leaked files from NSA servers. A collection of workable exploits had been leaked by the ShadowBrokers hacking group in April. Among this collection was an exploit called “ETERNALBLUE”. This exploit makes use of a flaw in the widely used SMB protocol in Microsoft Windows which is used for sharing files across a local network.

This is one trait that WannaCry and Sasser have in common, even though the two are not related in any way. It just goes to show that the use of the SMB protocol and its associated network ports in connection with malware is not something the makers of WannaCry have invented. In addition to this, Sasser struck before the days of automated Windows updates. A fix for the underlying security flaw had been available for quite a while - but since users had to download and install the patch manually, it was not installed on may PCs. Had updates been automated like they are today, Sasser or Blaster would not have had the impact they had.

Ironically, the SMB security flaw which had been stockpiled in a collection of NSA tools was fixed by Microsoft as early as March. Microsoft was aware of the flaw earlier, which has contributed to them skipping February’s patch day in order to give them more time to fix it. Any systems which had applied the March update were not susceptible to attacks by WannaCry.

A legacy for generations

Any machine which did not have the update was in serious danger of being infected – this forced some companies to take drastic measures. In some organizations, employees were asked to shut down their computers and stop using them in order to stop the infection spreading throughout the network. Unpatched machines were not the only ones falling prey to WannaCry: the vulnerability remained unpatched on Microsoft’s legacy operating systems, such as Windows XP, Server 2003 and Windows 8. That is, until Microsoft decided to go out of their way and release an emergency update for the aforementioned systems. After all, Windows XP has remained a permanent fixture in many critical environments such as hospitals, where it is still used to control medical devices and for daily operations. There are several reasons for this which we will go into later in this article. Hospitals are especially problematic in cases like this. In Britain, the NHS has declared the event a “major incident” – doctors and nurses were thrown back more than 20 years within hours, as they were unable to use their computers and had to go back to using pencil and paper.

There are now many questions surrounding the events. The success of the infection wave has made it painfully clear to many that failing to install updates can have severe consequences and possibly earn them a space in national headlines.

A lesson in humility (for the attackers)

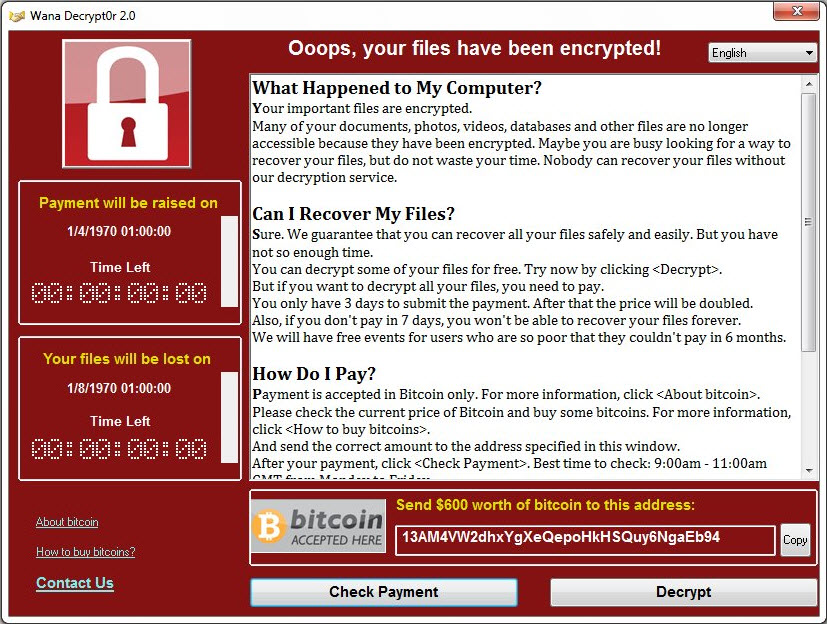

It is pretty apparent that the makers of WannaCry were overwhelmed with the outcome of their campaign. If they planned to decrypt files at all, they have chosen a poor system to keep track of payments made as well as starting the decryption - both are processes which require manual intervention on the attackers' part. This would lead to severe delays in processing payments and starting the decryption - and undesirable characteristic for a system that is supposed to make large amounts of money very quickly. To date, only around 100.000 dollars in Bitcoin payments could be traced to the attackers' wallets. This is a minute sum given the large number of infections. Even if only 2.5 per cent of all victims paid the ransom, one would expect to see at least fifteen times that amount.

However, attribution is a notoriously difficult thing to do. Some evidence seems to link WannaCry to an APT group with ties to the North Korean government - a claim that we have yet to see conclusive evidence for. The way things stand now, an attack group has gotten their hands on quite a powerful tool without any idea of how powerful it would actually be. A fitting picture might be a person who expects a trickle from a garden hose but suddenly finds himself facing a high pressure fire hose that blasts him across the room.

We are not done just yet

Even though the biggest wave is slowly ebbing away, the next one already appears to be on its way: reports have emerged about a massive DDoS attack against the killswitch domain. The objective appears to be to breathe some new life into WannaCry by preventing targeted machines from contacting the killswitch domain which would disable the malware and stop it from infecting the system. On top of this, more government exploits have been leaked which appear to be in active use at this point.

Why patching is not always an option

Everyone agrees that staying away from legacy systems and installing critical patches are two of the most powerful tools to prevent bad things from happening. However, it would be too easy to dismiss the affected parties as being foolish or negligent. The problem of legacy software in critical environments runs a lot deeper and is usually not a result of laziness or negligence. Regulatory restraints as well as budget issues are at play here. Let’s take hospitals as our example. Many medical devices need to undergo a certification process before they are allowed on sale and be used for patient treatment and care. Those certification processes are very lengthy and come with a hefty price tag. Any software updates for those devices often can only be performed by certified specialists so the device retains its certification. Those updates are few and far between and can cost six-figure sums and a couple of days to perform, during which time the machine is not in service. Updating such devices is rarely a matter of just downloading a file and clicking on it. For instance, if you were to purchase the newest MRI machine from a leading manufacturer right now (May 2017), it will run Windows 7 – if you are lucky, it will be Windows 7 with Service Pack 1. So you just cannot buy many of those devices with an up-to-date operating system. Previous generations of the same devices are likely to run Windows XP. In less than three years, Windows 7 will go the way of Windows XP and will not be supported by Microsoft anymore.

One would be tempted to say “Well, just replace the thing, then!”, but there are two major problems with that: first, Windows 10 is unlikely to run on those modern machines any time soon, even though a certification process may already be underway. Second, hardware like a top of the line, state-of-the-art MRI machine (or a modern milling machine or other kind of complex hardware) costs several million Euros, including the required structural changes to the building it is supposed to go in. So machines like this are a long-term investment which is likely to remain in service for years, sometimes a decade or even longer. During that time the manufacturer of the device may go out of business or just declare the “end of support” for the device in question, both of which means that the machine is not going to receive updates anymore.

Other industries do not fare any better: some industrial equipment like milling or welding machines face the same problem. On many shop floors you might still find that a Windows NT or Windows 2000 machine controls the equipment. Therefore some customers customers cannot “just patch” those machines - if you want to find them guilty of anything, then it should be of a lack of proper segregation for those machines.

This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.

5 tips on how to prepare for "the big one"

Update as frequently as possible

This tale has also been told ad nauseam: updates for installed programs as well as the operating system should be applied as quickly as they are released, especially if the update is considered to be critical for maintaining or restoring security. Home users have it easy: Windows updates run automatically for the most part, so no further action is required there. In a business environment, a patch management solution will help to maintain a higher level of security. This becomes more important the bigger the network becomes. If updates cannot be performed for any reason, other measures must be taken to ensure the safety of the rest of the network (see #3).

Have an up-to-date AV solution

If a new ransomware hits the streets, the chances are very high that your AV solution already knows it. AV software has several ways to detect malicious programs such as ransomware, apart from the classic signature. Proactive technologies can really help improve the level of protection from such threats even in case there is no signature available yet. Behavior monitoring by now is part of most security suites. In G DATA’s case, a dedicated AntiRansomware module offers additional protection.

Perform Network separation

If it is possible at all, air-gapping would be ideal. This may not prevent an infection from occurring, but at least an outbreak will be confined to one area as opposed to spreading all over the network. In a hospital, an outbreak would “only” affect medical imaging, but leave other departments unaffected. That way, doctors would not have needed to go back to pencil and paper and still have had access to existing electronic patient records. In the case of WannaCry, hospital staff in the UK even had to turn non-critical patients away because they had their hands full with keeping the more critical patients alive – sometimes in the very literal sense of the word.

Network separation again comes with a set of challenges. Here we are facing a conflict of interests between keeping everyday operations running smoothly and at the same time make them as safe and secure as possible. Air-gapping a network would have been a good solution for this. If a device has no physical connection to a network, things like WannaCry would not have been able to spread. But, to stay with the hospital example, medical imaging with modern devices has the great advantage of just shoving the images into a pool where a doctor can pick them up and review them. Of course, this is grossly oversimplified, but you get the idea: some sort of network share is required which means that there needs to be at least one point of contact between the two networks that harbor imaging machines and the one used by the doctors. A worst case scenario would be a flat network hierarchy, where all those devices are on the same network – that’d be an ideal spreading ground for WannaCry.

Train your employees

While training is not everybody's favorite topic, it might make the difference between operations coming to a complete standstill and operations going on with only minor disruption.

If employees know what to do in an emergency, things are way less likely to go wrong - just an example: an employee, has, unbeknown to him, infected a flash drive with ransomware. At home, stores a file on the stick to print out at work. At work, he plugs in the stick and the system is encrypted and locked immediately. Instead of taking the USB stick to the next computer to print his document "because his computer is broken", he should know that he should contact the right people immediately and stop whatever he is doing right now. On that note: threatening dismissal in case of such events might even be counterproductive - if an employee knows that he will 'get the sack' if he does something like that, he is more likely to try and keep the affair under wraps (or worse: try to fix it) until it is too late.

Get outside help for emergency procedures

Developing a good incident response strategy can save your organization a lot of grief. Therefore it makes a lot of sense to get some external expertise on board to help formulate a strategy. This is not a trivial thing to do and many factors must be taken into account here - but the effort will be worth it, if "the big one" ever hits.