What is the issue?

There are multiple vulnerabilities in a library in the Android operating system used for displaying media content. The Stagefright engine is used for recording and playing back audio and video files. Attackers can use these vulnerabilities to exploit audio and video files and run (malicious) code on the particular device without the owner's permission. This can happen automatically in the background without the user's knowledge or help.

What makes these vulnerabilities so bad?

There is at least one possibility of attack where a user is (almost) defenceless, as no user interaction at all is needed between the attack and execution of the malicious function. The attackers simply need to send a specially manipulated MMS to the device under attack; the attackers can then hack the library mentioned as the MMS content is automatically loaded onto the phone (enabled by default). They then have the option of running various malicious functions on the device where, in combination with other exploits, they can also acquire root permissions.

In doing so the attackers might even delete the MMS immediately after the successful attack, so that the user basically has no hope of noticing the attack at all. Alongside this problem with MMS attacks that is currently the subject of much discussion, further background information concerning Stagefright was presented at this year's BlackHat conference.

Why is the user "almost" defenceless? What can he do?

Closing the vulnerabilities in the operating system's source code is a job for the device manufacturers. They need to carry out repairs here and provide updates for the devices concerned. One particular problem is that the holes do not only need to be closed in the Android operating system. Many providers of mobile devices have carried out specific adaptations and now need to update their operating versions.

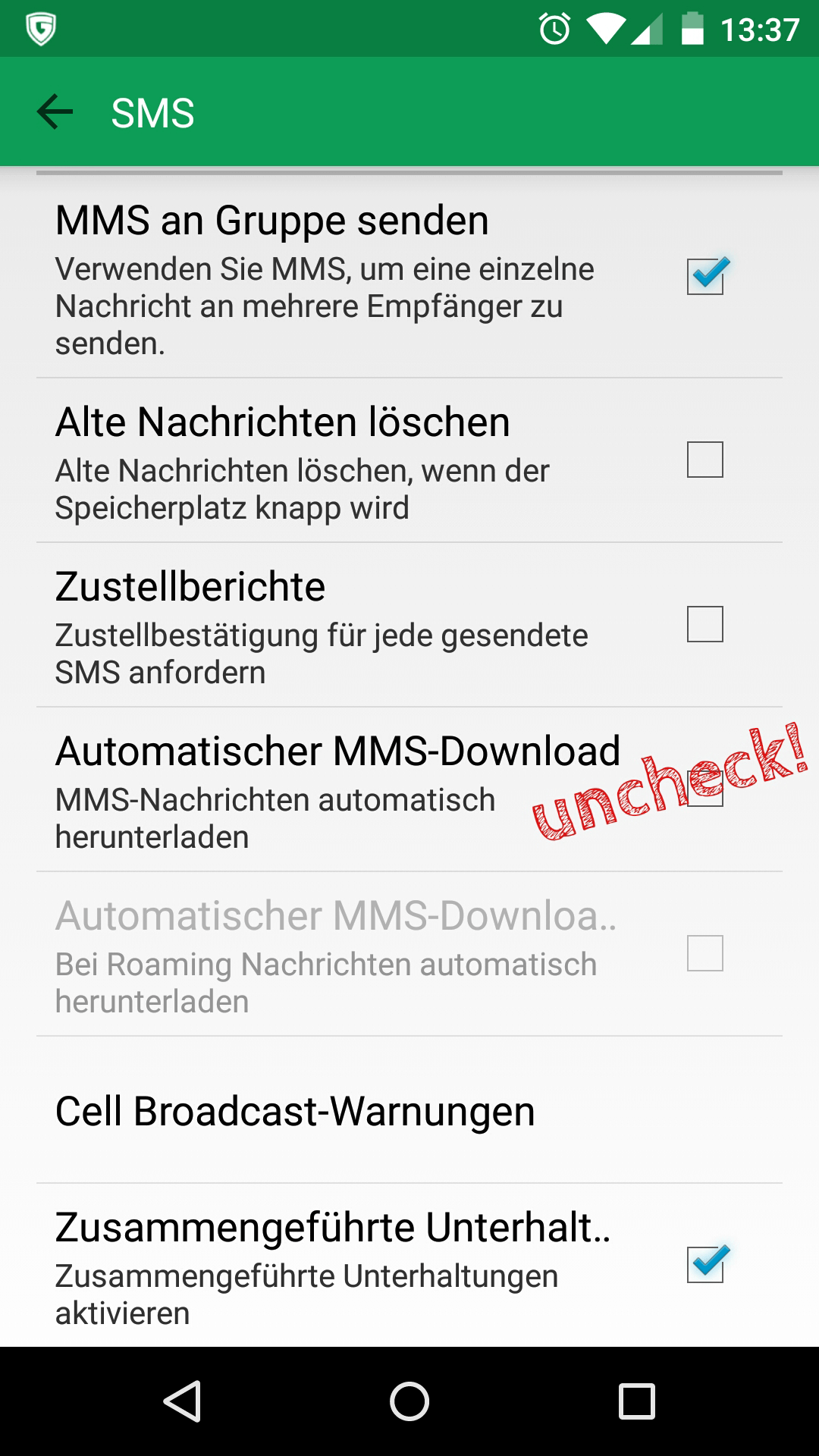

There are two mitigating steps that offer some protection against the MMS attacks described:

- Automatic loading of MMS content needs to be disabled on the device.

- Users need to block the receipt of text messages from unknown senders wherever possible.

Even so, the options of other attack vectors remain unaffected by this, so users can only hope for a fast response from the device manufacturers.

Who is affected by the problems?

Initial reports concerning the security hole state that "Android and derivative devices after and including version 2.2 are vulnerable. Devices running Android versions prior to Jelly Bean (roughly 11% of devices) are at the worst risk", says the report. In practice, however, it makes little difference if a version is affected or seriously affected, as all are vulnerable. The CERT Division of the Software Engineering Institute is providing a list of affected devices.

No publicly acknowledged attacks have been registered to date "in the wild"; however, there is evidence that the attack code has been circulating in underground forums for some weeks now.

How long has this vulnerability been known about?

The current reports point to a publication date of 27 July 2015. However, a user called Droopyar who is well-known in Android developer circles claims that information about this vulnerability has been around since March.

What does this mean for the future?

According to scientists, the Stagefright engine is clearly "not the only vulnerable component".

The important innovation with these attacks is that smartphones and tablets can be infected automatically and without the user noticing. To date, the only way of transferring malware onto a smartphone was to get the user to install (malicious) software. This is no longer the case. We are assuming that attacks in which user interaction is no longer required for an infection will soon be used by attackers. This means that a new range of attacks has opened up and that protecting mobile devices is even more important than before.

Can anything positive be drawn from this event?

In fact there is a notice on Google on this matter from which a positive outcome to this event can be drawn: now, "own-brand Nexus devices will receive regular OTA (= over the air, wireless) updates each month focused on security, in addition to the usual platform updates", the official Android blog reports.

Furthermore, Nexus devices will in future receive two-year major updates and three-year security updates (calculated from when a model is first put on the market). If a range of models in the official Google Shop expires, users will receive security updates for another 18 months after the last day of sale.

However, users of devices from other manufacturers continue to be directed to their update policies, which sometimes involve huge time delays until the all-important code is delivered. This leads to security-related disadvantages for these users, as we have already forecast in the G DATA Malware Report H1 2011.